Rodger Williams

June 12, 2025

Most people assume that public schools protect students because the schools’ mandatory reporters contact Child Protective Services (CPS) about suspected child abuse. That assumption is wrong.

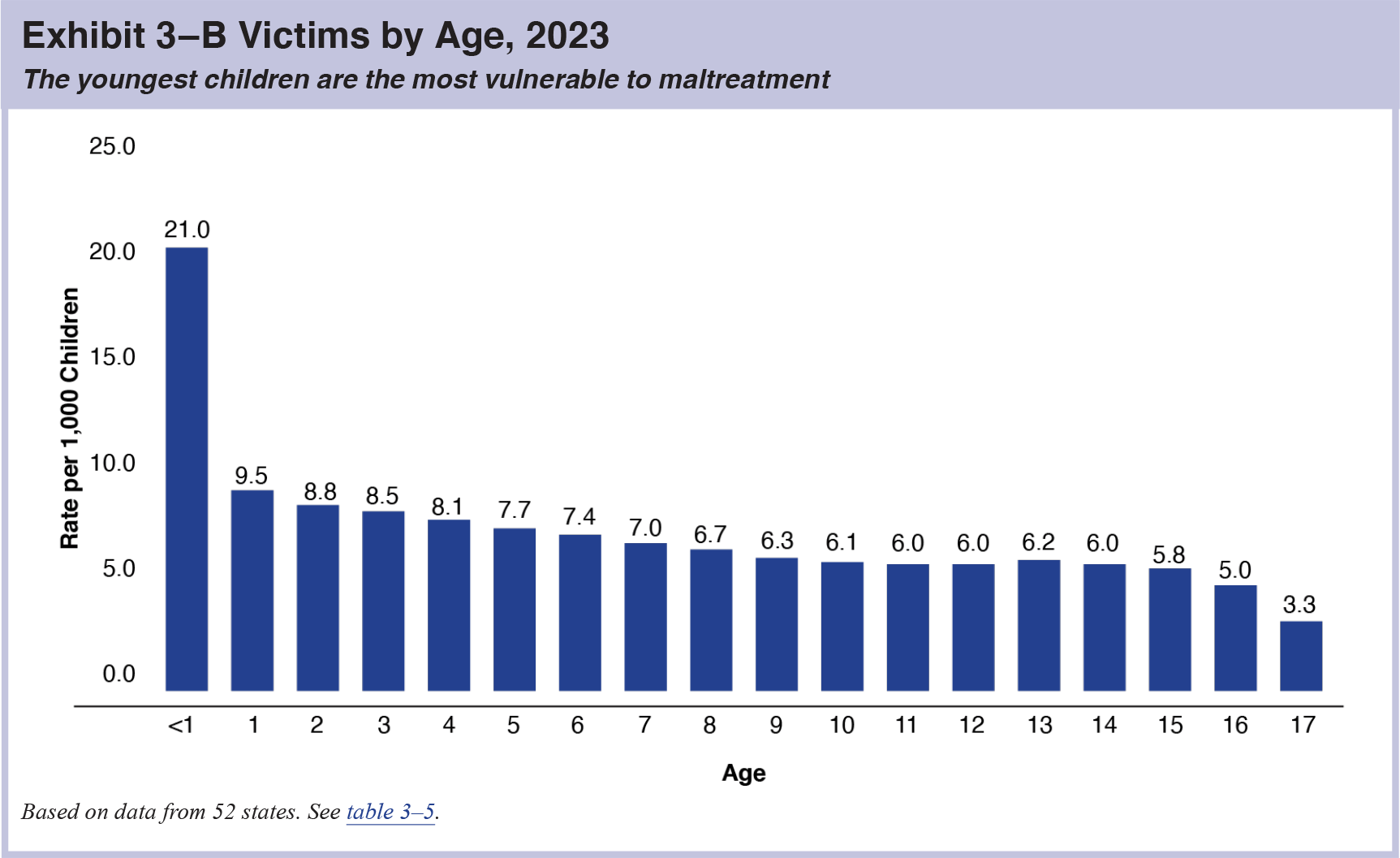

Federal child abuse data displays no protective effect as children enter public schools. Abuse rates continue a gradual descent as children get older. There is no visible dip in abuse rates as children cross the line between not being in school to being in school.

Child Abuse by Age 2023

Graph reproduced from Child

Maltreatment 2023, p. 27

85% of students are in public schools. If public schools were protecting their students there should be a dip in abuse rates when this large group of children enroll in school. But that dip is missing. It has been the same pattern since HHS started graphing these statistics in 2012.

How can this be?

Public schools detect and report possible child abuse to CPS. CPS then prevents further abuse. That is the theory.

But research does not show CPS preventing child abuse.

Russell, Kerwin, and Halverson (2018) using California data found that providing CPS services did not change the likelihood of future child abuse:

The purpose of the current study is to examine whether opening a case for services is directly related to the likelihood of future child maltreatment. The results of the current analysis demonstrated no relationship.

For cases with a similar high risk of a future substantiated referral, opening a case for services has no observable effect on the actual rate of future substantiated referrals. Outcomes for similarly situated families for whom the revised risk assessment recommended case opening were the same regardless of whether the case was opened for services…

Together, these findings suggest that opening a case for services does not change the likelihood of a subsequent substantiated referral for a family. For all families, case opening did not divert families away from their initial risk of a subsequent substantiated referral.

Fuller and Nieto (2014) using Illinois data found that in cases where CPS provided services there was an increased risk of future reports to CPS of suspected child abuse compared with matched cases that did not receive services:

Results indicate that even after matching, families who receive child welfare services are almost twice as likely to be rereported to child protective services as families who do not receive services….

Results of the current study suggest, however, that even after equalizing pre-treatment levels of risk, families that receive services are significantly more likely to be re-reported to child protective services than those who do not.

Gautschi and Lätsch (2024) in an umbrella review of 44 publications about reducing child abuse in high-income countries found that results were not visible.

We found that a large number of publications included in this review did not find significant positive effects of the interventions studied at all, and those that did find positive impacts typically reported Cohen’s d‘s of around 0.1 to 0.3.

Jacob Cohen in Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences (2nd Edition, 1988) defined what values of Cohen’s d mean in terms of effect sizes (in our case the difference between having interventions vs. having no interventions).

SMALL, d =0.2

“Small” effect sizes must not be so… large as to make them fairly perceptible to the naked observational eye.

MEDIUM, d=0.5

A medium effect size is conceived as one large enough to be visible to the naked eye.

LARGE, d=0.8

grossly perceptible and therefore large differences

A fairly big number of the 44 publications in the umbrella review showed no significant reduction in child abuse due to interventions. And those publications that did find positive impacts mainly found the results to have a Cohen’s d of around 0.1 to 0.3, with a value of 0.2 being a small effect that is not visible to the naked observational eye.

So now we see why the graph above shows no visible change in the child abuse curve as children move into public schools. The schools may report suspected child abuse to CPS, but there is little evidence that CPS is effective in preventing further abuse. The system fails to visibly protect public school students from child abuse.